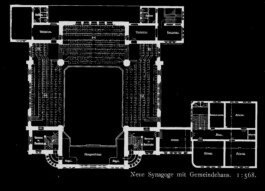

The synagogue

After the foundation of the German Reich, Düsseldorf developed at an extraordinary pace to become a large and industrial city. The population rose from around 70,000 in 1871 to 100,000 in 1883. By 1900, this figure had already more than doubled and stood at over 214,000. Parallel to the general population growth of the city, the number of Jews grew between 1850 and 1900 from 500 to a good 2,000. And so it is hardly surprising that the synagogue from 1875 had already become too small by the end of the 1880s. Since 1893, on the High Holy Days, when the number of people attending the synagogue was known to be larger, additional services had to be held in the rented hall of a public house. “This was a state of affairs which was unworthy of the community and which required urgent action.”

In 1899, a plot of land was finally purchased in Kasernenstraße - barely four hundred metres south of the old synagogue - for around 300,000 Reichsmark (RM). It did not entirely meet the wishes of the community as there were issues with the ground plan and the correct alignment of the Torah ark at the east end of the synagogue (in Kasernenstraße), which was also the frontage, i.e. the visible side. The community covered part of the land and construction costs with the proceeds from the sale of its plot in Bongardstraße in Pempelfort, where its cemetery had been located from 1788 to 1877.

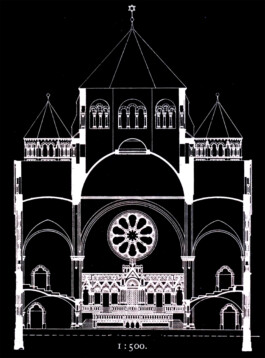

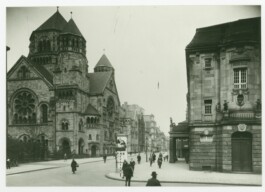

The synagogue in Kasernenstraße (Düsseldorf city archive)

Construction of the synagogue

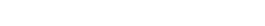

The Düsseldorf synagogue was built according to the plans of Joseph Kleesattel in the Romanesque style. Neo-Romanesque was the predominant style of synagogue architecture in the 19th century. In their difficult search for a suitable style of synagogue architecture, there was a period when the Jews believed that the Moorish or Byzantine style provided the best expression of the courage to create something individual, something independent. Yet on the other hand, it seemed to emphasise, albeit unintentionally, the foreignness, the oriental origin of the Jews. Many communities were keen to avoid this impression. Furthermore, they came to the conclusion that it was an illusion to consider the Moorish style as representative of a distinctly Jewish architecture. The neo-Romanesque style seemed to provide the best expression of the will to integrate, the aspired adaptation to the Christian environment, its history and its architecture: “Why shouldn’t a German Jewish community build its place of worship in the German style?”

The foundation stone was laid in September 1902. After two years of construction, the consecration was held on 6 September 1904. The synagogue had 780 seats for men and 550 for women; later, an additional hundred seats were created by rearranging the pews. The construction costs amounted to RM 450,000, the cost of the interior furnishings was RM 125,000.

In December 1904, the lllustrirte Zeitung published in Berlin featured a beautiful picture of the synagogue. The accompanying text read:

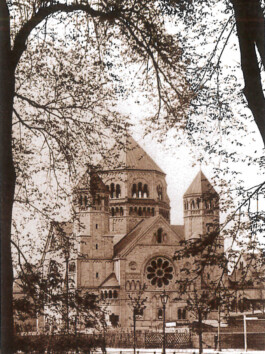

“Düsseldorf, the art metropolis on the Rhine, has gained a further addition to its numerous magnificent monumental buildings in the form of the recently consecrated new synagogue. With this elegant building, Professor Joseph Kleesattel in Düsseldorf, the acknowledged master of church construction, has given Düsseldorf’s mighty Rochus dome a counterpart in the same Romanesque style. Together with the community hall and school building, which is connected by an arched open passageway, the building with the two flanking towers in Kasernenstraße, the imposing two-storey crossing dome and the protruding entrance halls form a monumental group of buildings characterised by dignified beauty and calm nobility. In accordance with the ritual requirements, the synagogue is situated with the Holy of Holies facing due east. The visible exterior surfaces and all architectural elements are made of light-coloured Vosges sandstone, while the foundation and the steps are in basaltic lava from Niedermendig. The interior is designed in light, simple colour tones that allow the natural material to achieve its full effect.”

The synagogue shortly after completion, 1904 (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

The synagogue shortly after completion, 1904 (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

For the weekly service, the ‘small’ synagogue was used, which was located on the lower floor on the street side and was directly accessible from Kasernenstraße. Many former Düsseldorfers remembered it as the ‘Polish’ synagogue as it was made available to the Eastern European Jews as a place of prayer during the Nazi era.

Use of the synagogue

Many former Düsseldorfers adhered to their synagogue with pride and love, not least because of the musical arrangement of the service, which included a permanently employed choir and organist. Nobody minded that the choir had non-Jewish singers for years and that the organist Karl Mingers was also not Jewish. It was not until the end of 1935 that the Nazis caused them to leave.

View of the inside of the Düsseldorf synagogue in Kasernenstraße (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

From 1924, the synagogue also occasionally opened its doors to the wider public. It hosted annual cycles of lectures with prominent speakers from all over Germany. They were a means of informing people about Judaism and Jewish history.

In the spring of 1935, the Jewish school was set up in the house of the rabbi, which was soon attended by 400 children.

Unnoticed by the non-Jewish public, concerts and other cultural events were now also held in the synagogue, which only Jews were allowed to attend. While until 1933 “Jewish culture” was almost exclusively confined to the religious sphere, the Jews were now compelled by the new rulers to establish a cultural counter-world: culture by Jews for Jews as a forced and then self-willed response to the Nazis’ policy of exclusion.

In those difficult years, the synagogue increasingly became a bastion where people sought protection, comfort, help and distraction.

For many Jews in Düsseldorf at that time, the recitals given by the great Russian-Jewish singer Alexander Kipnis in March 1934, March 1935 and February 1937 were also unforgettable. At his first concert, all 1,400 seats in the synagogue were sold out. The first winter concert was to be held in the synagogue on 13 and 14 November 1938 - with a chamber orchestra, female and male choir. But it never took place.

The synagogue before 1938. The theatre on the right of the picture (Düsseldorf city archive)

Anti-Jewish graffiti on the synagogue façade, 1929 (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

Background - The year 1938

Interview Ellen Marx with Angela Genger

Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf

“We were all sleeping, my parents had a bedroom, and I slept with the maid. And all of a sudden, the door rang, and there were maybe fifteen or twenty [people] in uniform, and they all shoved us into my bedroom and destroyed the apartment, to such a degree I just cannot explain to you. We had a living room, a dining room, my father had an office, a hallway. They threw every piece of furniture out of the window. The window frames, everything was broken; I have never seen anything like this in my life. We just heard it, and at one point, we came out, and in the kitchen, we had a wall with a birdcage. I think this stuck with me always, and my father loved animals and birds. They took a knife and killed all the birds, and then they took eggs and threw them against the wall. The birds and the blood and the egg yolk running down the walls. It’s something I’ve never forgotten. The apartment was empty; there was nothing left in the apartment. And the next morning, maybe around 9 or 10 o’clock, my mother was in a state of shock, and everything was in front of the door; they burned everything.”

On 26 March 1938, Düsseldorf’s rabbi Dr. Max Eschelbacher (1880 - 1964) celebrated his 25th year of service in Düsseldorf. He had moved there at the age of 33 with his wife Bertha and their two sons on the suggestion of Leo Baeck as his successor. At the time of this celebration, the family, which later extended to four children, had already been separated for years: their son Leo practised as a doctor in the United States; the second eldest, Hermann, was a temporary research assistant at the Encyclopedia Britannica and was trying to establish himself as an antiquarian bookseller in England; their son Joseph-Ludwig was scraping a living on a farm in Argentina, far removed from European city life; and, after finishing school, their youngest daughter Marianne, started training as a nurse in England in 1935. The family gathered together again for the last time on the occasion of the parents’ silver wedding anniversary in 1935.

First wave of emigration

Most Jewish families in Germany fared the same as the Eschelbachers: those who were young enough and had the connections and means to emigrate left their homeland and tried to gain a foothold in another country. Around half of Düsseldorf’s community members (5,624 in 1933) took this path, mostly at great financial cost. Others, such as the second rabbi Dr. Siegfried Klein, made a conscious decision to stay with the community. Special taxes, e.g. the Reich Flight Tax, regulations on foreign currency, etc., severely restricted the freedom of action of those who remained in Germany. From April 1938, Jews were obliged to declare assets of over RM 5,000, the basis of the expropriation which, among other things, later reached its first absurd climax on 12 November 1938 with the ‘atonement payment’ of RM 1.127 billion. The Düsseldorf community was required to pay one million RM for this. Insurance companies paid claims directly to the German Reich (totalling RM 225 million), while the injured Jews were left empty-handed.

The Eschelbacher family in Düsseldorf in 1935. Dr. Max Eschelbacher (1880-1964) and his wife Berta, née Cahn (1884-1962) at the bottom, the children at the top: from left to right Hermann (1912), Leo (1911-1958), Nanni (1921) and Josef-Ludwig (1919-1968)

The rabbi Dr. Siegfried Klein (1882-1944) and his family: wife Lilli, née. Plotke (1895-1942), daughter Hanna (1923) and son Julius (1925)

Another issue that worried Rabbi Eschelbacher was that a law passed on 1 April 1938 stripped the Jewish communities of their legal form as public bodies and declared them to be associations with legal capacity. Shortly after this, in June of the same year, a range of community representatives were taken into police custody, and other community members were placed in “protective custody”, mostly for offences that were either entirely fabricated or long since lapsed, such as driving licence offences or similar.

Further measures from September 1938 saw the withdrawal of licences for Jewish doctors and, a little later, the few Jewish lawyers who were still permitted to practise, further impoverishing the Jewish population along with the tightening of legislation on “Jewish businesses” from January 1938.

“The Polish action” and the “assassination”

It was against this background that attentive observers witnessed the first deportation from Düsseldorf: on the night of 27 October 1938, police officers took around 461 people from their homes: men, women and children who, after a brief stop at police headquarters, were loaded onto trains as “Polish Jews” and transported to the Polish border in Zbąszyń (Bentschen). They included a considerable number of women who had only become Polish citizens through marriage, as well as their children. At first, the Polish authorities refused to let the deportees in, and only very few were able to return.

In an act of desperation, Hermann Grünspan, a member of an Eastern European Jewish family deported from Hanover, shot the German embassy employee Ernst vom Rath at the German embassy in Paris. Mortally injured, he died a few days later and the National Socialists used this as a pretext to launch a pogrom throughout the German Reich.

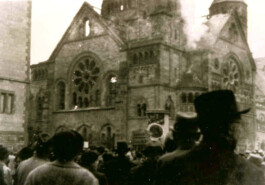

The pogrom night

The pogrom night from 9 to 10 November 1938 was to go down in history as the biggest ever assault on the German Jews living here. This attack was well prepared, the SA and SS squads worked on the basis of prepared lists. In Oberkassel, a district on the left bank of the Rhine, nothing happened to start with because the official in charge was at an NSDAP party and had locked the list in his desk. The crimes that unfolded before everybody’s eyes ranged from murder, manslaughter and assault to arson, robbery, looting, property damage and finally the arrest of many. According to the Düsseldorf police detention register, 155 men and youths and 20 women were held in the police prison. The youths up to the age of 16 and the women and older men were released after one to three days. The others were put on a train on 16 November 1938, which took them to the concentration camp in Dachau. They were only released from there if they were either urgently summoned to liquidate or “Aryanise” a business or if they were able to produce emigration papers. Most of the detainees returned to Düsseldorf after three to six weeks. The relatives remember it as taking months. Such was the physical and psychological impact of the imprisonment on the fathers, husbands and sons.

The pogrom night in Hüttenstraße (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

The pogrom night in Hüttenstraße (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

Synagogue on fire (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

Synagogue on fire (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

Three people lost their lives in Düsseldorf on the night of 9 to 10 November 1938, another four died soon afterwards from the effects, five took their own lives in despair and others were left with health damage from which they never recovered. 70 people had to be admitted to hospital, including the seriously injured Salo Loeb, who had been stabbed more than twenty times. To protect him from arrest and deportation, doctors and nurses at the Catholic Marienhospital did not even inform his relatives of his whereabouts, so he was initially presumed dead. After he was discharged from hospital, Salo Loeb was repeatedly arrested by the Gestapo, released for a few days and then arrested again. This ordeal only ended when he was able to emigrate to the USA with his family in 1940, literally at the last minute.

Dr. Max Bergenthal at the end of the 1930s (collection of the Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

Interview John Delmont with Angela Genger

Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf

“We were with friends, my parents in the Zoo district in Düsseldorf. In the evening, when we were leaving, we saw that the synagogue was on fire. When we got home, the phone rang. My father was called out to people who had been attacked with knives and so on. He came back because he didn’t have enough bandages and said: You have to get out! Then my mother and I went through the Hofgarten. The SA were already standing there, as if on parade. Then we went to a colleague of my father’s who was Aryan, Dr. Bischof at Königsplatz, now […] Lutherplatz. They took us in despite the extreme danger it put them in. We waited until 4 o’clock in the morning to see if my father was still alive. He went from one patient to the next and then to the Marinen Hospital. We stayed the night with the colleagues and when we went back in the morning, there was of course nothing left but rubble. They had smashed everything.”

Aftermath

Bunker on the synagogue grounds, 1940 (Düsseldorf city archive)

On 11 November 1938, the building inspectorate decided that the remains of the synagogue had to be demolished for safety reasons. The city administration was to arrange for the demolition, “and then, once the work was completed, efforts would have to be made to recover the funds from the state.” This makes it quite clear that at least this authority initially held the opinion that the state should pay for the damage was responsible for. One day later, however, the ‘Ordinance on the Restoration of the Street Image in Jewish Commercial Operations’ was issued. This obliged the owners and beneficiaries of the destroyed ‘Jewish property’ to repair all the damage themselves or to demolish any businesses that were in a state of disrepair.

Thus, on 22 November, the Jewish community was told that they had to start with the demolition within 24 hours - because of the danger to road users - and because they were ‘defacing the surroundings’. Otherwise, the demolition would have to be carried out by a third party by means of administrative enforcement and a provisional advance on costs of RM 24,000 would have to be collected from the community. The community council responded on 23 November: the building was currently requisitioned by the Gestapo and they were unable to enter the property or make any decisions. The answer was: this was not the case, 24,000 RM had to be paid immediately.

In the meantime, however, on 21 November a demolition contractor had submitted a cost estimate of RM 20,500 to the city authorities, which included all the works. He had added: the salvaged materials were not to become the property of the company, they would remain the property of the city. After a meeting on the same day, during which the contractor presumably found out that the Jewish community and not the city or the state would have to pay the demolition costs, he quickly typed out a new, much higher cost estimate totalling 37,000 RM.

On 2 December 1938, the people of Düsseldorf were able to read in the Rheinische Landeszeitung: “The synagogue in Kasernenstraße, which has been a thorn in the side of all fellow Germans for many years, is now soon to disappear. It is to be hoped that the Jewish school will be pulled down at the same time. The population of Düsseldorf wishes that nothing be left remind them of the times when Judah brazenly reared its head in Germany.”

Following completion of the demolition work, the building contractor received his 37,000 RM. He had even removed the foundations of the former barracks, brought in topsoil and levelled it nicely so that grass could grow over everything. After all, the Lord Mayor had ordered the “creation of a reasonably respectable appearance in the city centre”.

Before the November pogrom, the value of the synagogue and the grounds had been estimated at almost 800,000 RM. The assessed value of the plot alone was RM 360,000. The city authorities deemed a purchase price of RM 150,000 to be sufficient. Even the real estate agent W. Mockert, who was engaged by the community and who pointed out its great financial difficulties, was hardly able to achieve anything. After humiliating negotiations, the community was compelled to sell for RM 191,870. From this amount, however, the city deducted another 75,000 RM: 37,000 for the demolition, 26,000 for the construction of a car park which had been completed in the meantime and 12,000 for this and that. The community was left with the ridiculous sum of 84,970 marks and 34 pfennigs, and had to wait until the end of June 1939 for the payment.

The city had been in possession of the property since 30 March 1939. At the start of the war, an underground bunker was built on the plot, which protruded about three metres above the ground. After the end of the war, the bunker was converted into a hotel, which received the somewhat shamefaced nickname “Abraham’s lap”.

Commemoration at the memorial in Kasernenstraße, 1946 (Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Düsseldorf)

In the middle of the 1950s, restitution proceedings took place between the Regional Finance Office in Düsseldorf and the Jewish community and the Jewish Trust Corporation. The city remained the owner of the property, which was used as a car park.

View to the north towards the site of the former synagogue in Kasernenstraße, 1970 (Düsseldorf city archive)

At the beginning of the 1980s, it sold it to the Handelsblatt publishing group. The latter constructed a high-rise block there.

In 1983, the new owners had a memorial erected on the pavement right on the edge of the heavily trafficked, noisy Kasernenstraße. It refers to the re-establishment of the Jewish community after the end of the war. Most people driving or walking past overlook this memorial, even those who have come back to their former home town in search of traces of the past.

Synagogue memorial by Thomas Fürst, 1946

Interview with Ruth and Herbert Rubinstein and Mischa Kuball